Household formation was dullishly ordinary before it became the Australian 'dream'.

Do not exalt the worthy, and the people will not compete.

-- LaoZi, Dao De Jing 3

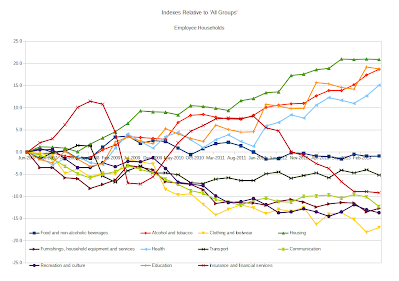

Non-discretionary spending like housing, health, and arguably education have gotten more expensive. Here's a chart I did a few years ago, (but it's not as if things have reversed).

You can focus on the chart lines going up and moan about how expensive essentials have gotten. (Waah! Junior can't get on the property ladder.)

The flip side is that yesterday's big ticket items are now a lot cheaper.

You can focus on the chart lines going down and rave about how cheap discretionaries have become. (Y'know, Nathan Rothschild didn't have broadband.)

Buying a home and raising a family are now success markers. But decades ago, when housing, healthcare, and schooling were much cheaper, that was just low-hanging fruit.

When asked, my parents said, shrugging, that having kids was just, "What you did."

While that did involve sacrifice, we need to see the sacrifice not through today's lens but through yesterday's. In that context, family formation wasn't so much biting the bullet and dutifully committing to six-figure school fees, but a relatively trivial coming-of-age ritual.

That mediocrity should become a source of pride and prestige is counter-intuitive. Extraordinary recognition should require extraordinary effort. You don't usually get a trophy just for showing up.

However, that's pretty much what my parents' generation did. Now, it's almost as if success became defined by what was commonplace.

That is not to say they had it easy. They had to contend with racism and sexism while pursuing those modest goals. The struggle was different, but the struggle was still real.

Nevertheless, this raises the question: what spending would have been exceptional in the 1970's and 1980s?

Very few of us who grew up then would have been able to brag of having a separate phone line for every person in the house, yet we don't make a big deal today about everyone having their own smartphone. Personal communications have become ubiquitous as they have become cheaper. Somehow, the narrative around this has turned negative: modern people spend too much time online.

The need to save for and carefully select durable clothes as been obviated by affordable fast fashion. My ability to change outfits every season (like folks in Paris!) would have left friends' mouths agape thirty years ago. Negative spin has also built up around this, decrying the choice of disposable over durable.

'Avocado toast', unsurprisingly, resonates with older critics as the cause of young persons' spending problems. Food was more expensive when I was young, and avocado was an almost unheard-of luxury. Not so now.

Such extravagance back then would have been signs that we had "rocks in our heads", not that we were living our best lives. Even today, we chortle at people who pay too much for something, so why should household formation, now expensive, remain sacred?

First things first. The young are not spendthrifts. From the Grattan institute:

The intergenerational wealth gap cannot be explained by too many avocado brunches. In fact, today’s young people spend only a little more than young people three decades ago – and the higher spending is mostly on essentials, particularly housing.

To fret that young people can't easily land what used to be slam dunks is an expression of compassion, I guess. But this misses that they are easily able to afford items that would have marked them decades ago as runaway successes. Younger cohorts are evidently, perhaps subconsciously, just as wise with their money, so maybe feeling locked out of homes and families comes not from a real need to meet those milestones, but from societal pressure frustrating rational reactions to price signals. And those price signals are screaming to not overpay for arbitrarily valorised items.

Those darn kids, buying what they can afford (but we couldn't). Let's put what we got at bargain prices on a pedestal and remind them to feel bad for not being able to attain it.

-- some fictitious Boomer

It takes time for people to get their head around relative price trends. So too, the moral values placed on consumption items seem to change slower than price.

That is unfortunate.

The solution to high prices is supposed to be high prices, in that it's supposed to change behaviour.

It's why department stores are dying. It's why drivers switched to petrol-sipping Japanese cars in the '80s. You're supposed to look at the sticker price ticking up and say, "Yeah nah, I'll get something else." (The price then crashes and makes market entry safe again for neophytes.)

High prices should make buyers sit on the sidelines, rather than insist on paying their parents' prices. High prices should make suppliers go bust if they cannot lower their costs. The default reaction to market failure should be to question whether that market is still relevant in its current form, rather than demand that the government prop it up.

Instead, narratives interfere, particularly narratives which add moral or status value, effectively de-commodifying items which would otherwise be freely traded on price. Double standards arise.

Buying negative yielding investments makes you a chump, but paying/borrowing extra for a 'good' suburb makes you conscientious.

That conventional goods are framed as resulting from hard work and tough choices muddies things. It's important to remember that paying a high price for something doesn't automatically make that thing worthwhile. Not all extraordinary effort warrants extraordinary recognition.

Thinking that price indicates value perpetuates over-valuation.

Rites of passage should not include martyrdom, and it is perfectly okay to abandon now-onerous success markers, particularly if they are now harder to attain than when it was decided they should be aspirations. Price change should spur behaviour change.

One solution: re-commodify everything in your own mind. Resist venerating housing, education, and healthcare as fundamental goods. Treat them as you would a barrel of oil or a bushel of wheat. If it promises future benefits, interrogate the ROI. Take hallowed items down a peg and you also take down the big displays made about buying them.

I realise that this approach isn't purely nihilistic, but goes towards idolising money itself.

So what? It's better than spending the rest of your life paying off items bid up because of their moral halo.

Furthermore, considering cost is a gateway to considering alternatives. And the chart shows that there are plenty of alternatives out there that are getting steadily cheaper over time.

There is evidence that frustrated home-buyers are pivoting to substitute purchases, like stocks.

Likewise, do not fear choosing to be a smartphone-sporting avocado-munching nomad. Ironically, that would have marked you as more successful (if also more eccentric) decades ago than choosing the conventional family life.

Comments

Post a Comment