Australian houses have gotten larger while Australian families have gotten smaller.

From Commbank's Home Size Trends report:

... houses are around 6 per cent bigger than 20 years ago and 27 per cent bigger than 30 years ago.

Australian house sizes have resumed growing, surpassing those in the U.S.

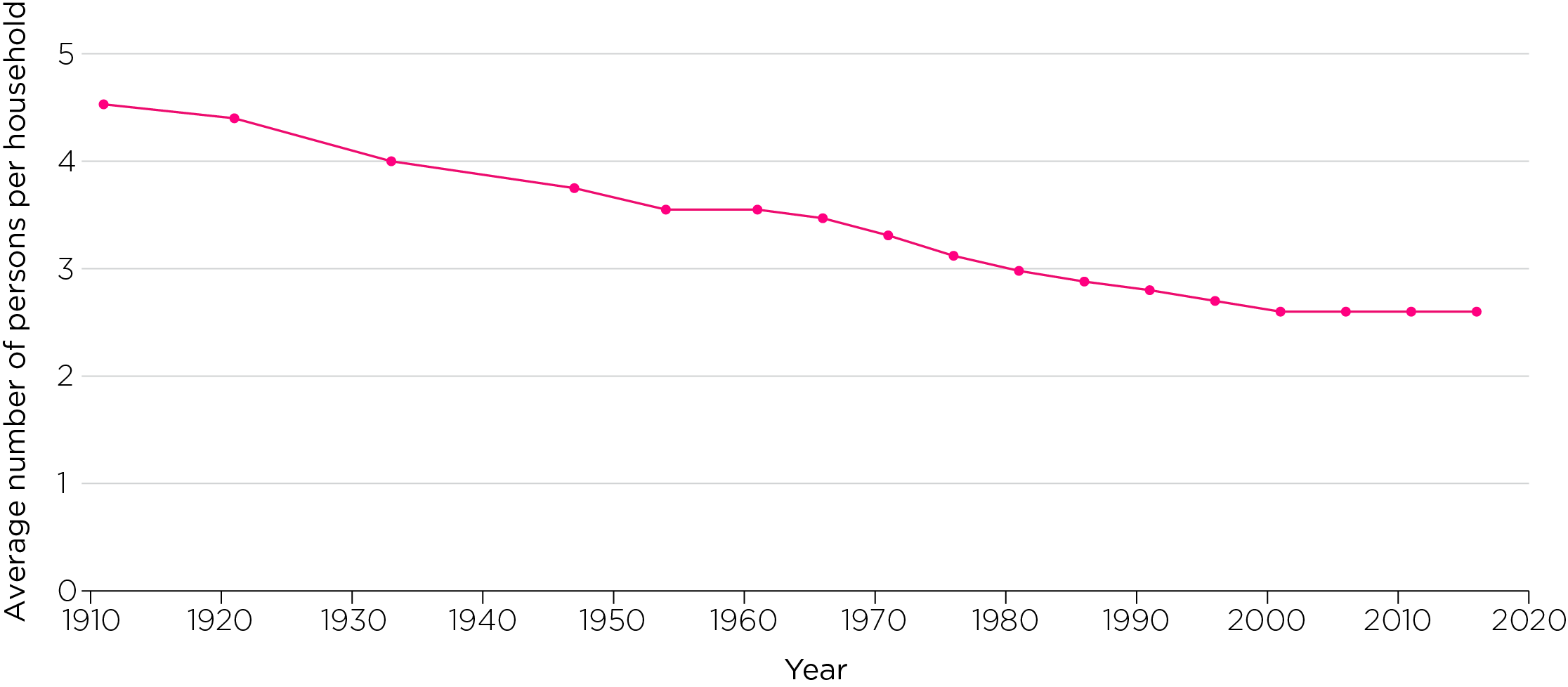

Meanwhile, household sizes have shrunk, with single-parent families and couple-only households become more common.

Households in 1991 had on average 2.73 members. Just under 30 years later, in 2016, they would have 2.55 members. A decrease of around 7%.So while house size per household has increased, house size per household member has increased more so.

Individuals are, on average, playing in 35% more space than they were 30 years ago in the early '90s. Expressed in compound terms, though it is not compound growth, that's around 1.03% p.a.

Australian houses aren't getting dearer just because they're getting bigger. Prices per square meter in Sydney, one of Australia's hottest housing markets, have risen about 7% p.a. in the 25 years to 2018. Quite strong, though underperforming the local ASX stock market, particularly if you subtract holding costs.

Though there has been some moderation in house and unit sizes over the past decade or so, perhaps motivated by sustainability and cost, there's a long way to go before we are back to the - relatively speaking - tiny homes of the 1980s and 1990s, in which larger families made do in smaller dwellings. In turn, there's a longer way to go to the per-person living spaces of the 1980s and 1990s.

These changes matter in debates around housing supply.

There are calls for more public housing to alleviate undersupply.

At the same time, existing public housing stock is under-utilised. There are surplus rooms but a shortage of houses. That is not to say public housing residents are living the life of Riley, but that the inefficiency flowing from unsuitability means others equally deserving miss out.

In both private and public markets, houses are larger than necessary, worsening affordability. Unaffordability is exacerbated if losing an earner, perhaps through relationship breakdown, is the reason behind a smaller family.

If you could snap your fingers and shrink homes 35% you could theoretically slash the equivalent from housing costs.

That wouldn't set living standards back to the dark ages, but the 1990s. (Enough with the Gen X jokes, OK?)

Before you judge, growing expectations are only partly to blame. The rest of the world makes do with houses that are are much smaller (and coincidentally cheaper). However, in my Adelaide suburb, most international floor sizes would be illegal. Consumers may want smaller homes, but be prohibited from them.

That being said, a return to 1980s floor sizes would not violate most planning rules.* Preference matters more than planning. Developers would not have voluntarily built larger than required without demand support from buyers.

Before house sizes ticked up alongside COVID-induced remote work pressures, Australians were coming around to the idea that maybe affordable housing meant smaller housing than we have experienced in our lifetimes; commensurate with our smaller households.

This is difficult because it is hard to frame shrinkage as anything but going backwards. Especially if others are flaunting their expansions at the same time. It is also politically charged, as public housing advocates would be reluctant to cede ground on 'minimum' living standards.

What would, I think, change minds is prolonged stagnation or falls in prices per square meter, turning size from a multiplier of gains into a multiplier of losses. I don't think net falls - where holding costs rise to exceed gains - will cut it. There actually has to be sticker price discounting.

Notes

* Based on Marion Council Development Plan. Sample Zone minimum lot size of 300 sqm with a minimum floor coverage of 60%. So 180 sqm.

Comments

Post a Comment