How closely Inflation tracks Unemployment, Wages, Immigration, Interest Rates (and Debt), Trade, Currency, and Industrial Action, in Australia.

Inflation scares a lot of people who remember the 1960s and 1970s with its double-digit price rises eroding savings, investments, and wage gains.

Since then, however, inflation and wages growth in the developed world has been low. Younger cohorts who haven't experienced rocketing prices (except in housing, education, and health) clamour for greater social assistance, particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, horrifying their elders who understandably fear that government largesse will re-awaken the inflation monster.

Putting aside whether and how much inflation is desirable, many causes have been suggested, including unemployment, wages, immigration, central bank interest rates, the availability of debt, trade, currency strength, and the bargaining power of labour. All are compelling theories, but let's take a glance at how closely they correlate with inflation.

Correlation Coefficient (r) values:

- 0 - no relationship;

- ±0.3 - weak;

- ±0.5 - moderate;

- ±0.7 - strong;

- ±1.0 - perfect.

TLDR⚡

| Factor | Correlation | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Interest Rates | 0.85 | Strong, but counter-directional to expectations |

| Household Debt | -0.63 | Moderate, but counter-directional to expectations |

| Unemployment | 0.06 | Almost no relationship |

| Trade | -0.12 | Almost no relationship |

| Immigration | 0.13 | Almost no relationship |

| Currency | -0.24 | Weak |

| Wages Growth | 0.56 | Moderate |

| Industrial Action | 0.77 | Strong |

Inflation vs Unemployment 🏝

- Measures: CPI year-on-year % growth vs Unemployment Rate, seasonally adjusted

- Period: June 1985 to March 2021, Quarterly

- Expected relationship: negative

The link between unemployment and inflation, described by the Phillips Curve, became fundamental to government price stability strategies to the point where, crudely, unemployment was used to control inflation.

At the very least, in the U.S. Fed Chairman Volcker tolerated the extreme levels of unemployment following extreme interest rates in the interests of dampening inflation in the 1980s (interest rates has its own section).

However, in Australia the high-inflation-high-unemployment 1970s and low-inflation-low-unemployment 2000s (1990s in the U.S.) showed the relationship was not as strong as thought, and may have weakened further in recent years.

Correlation (r): 0.06 - very weak

Inflation vs Wages Growth 👷♀️

- Measures: CPI year-on-year % growth vs Wage Price Index year-on-year % growth, seasonally adjusted

- Period: September 1998 to March 2021, Quarterly

The theory that unemployment dampens inflation begs the question whether wages are linked to inflation.

- Expected relationship: positive

After all, there are plenty more employed than unemployed, so it would be reasonable to expect that the aggregate actions of workers affects the economy more so than the behaviour of those not working.

Correlation (r): 0.56 - moderate

Which comes first - inflation or wages growth - remains unclear. Firms will not independently raise workers' wages (or share profits with them) simply because living costs more, or out of the goodness of their hearts. Workers must have the power to demand it.

At the same time, an incapacity to bargain up wages would cap how much you as a business could hike prices before people can not afford your product and forego it altogether.

To try and tease out the causal direction, let's look at other factors.

Inflation vs Immigration 🛂

- Measures: CPI year-on-year % growth vs Net Overseas Migration

- Period: June 1985 to June 2021, Annually

- Expected relationship: negative

If you subscribe to the theory that higher unemployment means lower inflation, it follows that more migrants leads to more workers for the same number of jobs, leads to more unemployed, leads to less inflation.

This concept prompts mainstream commentary about pandemic

travel restrictions leading to higher wages and inflation.

Dr Lowe said many firms were even trying to hold out until borders reopened.

If that didn't happen, he added, and borders were still closed a year from now, we would see more upward pressure on wages and inflation.

Correlation (r): -0.13 - very weak

Immigration, it is argued, doesn't just increase the labour supply, it also increases demand, putting upwards pressure on prices. Immigrants perhaps consume more than incumbents as establishing a new household needs more goods and services than keeping an old one humming along.

The weak correlation somewhat lets migrants off the hook, who would otherwise be blamed for low wage-push inflation or high demand-pull inflation. (They just can't win.)

Inflation vs Interest Rates 🏦

- Measures: CPI year-on-year % growth vs Overnight Cash Rate and Overnight Cash Rate y-o-y % growth.

- Period: June 1985 to March 2021, quarterly

- Expected relationship: negative (lower rates = higher inflation, and vice versa)

Conservatives like to warn about lower rates stoking inflation.

Nationals Senator Matt Canavan has urged the Coalition to turn its attention to inflation before it spirals out of control, accusing the RBA of adopting an overly “sanguine” monetary policy.

“We don’t want the inflation genie to come out of the bottle because he doesn’t grant you wishes. Once he’s out it’s too late.”

The theory goes that lower borrowing and investment costs will push up demand - and therefore prices - for goods and services.

Attacking the availability of money is based on the assumption that governments are incapable of putting it to 'good' use. It is hard not to see this talk of prudence as performative. The same critics remain silent when tax cuts are funded with the newly enabled deficit spending, but howl "big government" on proposals to increase welfare.

Correlation (r): 0.85 - strong positive, unexpected direction (OCR)

How to explain this counter-intuitive result? It's difficult to claim that higher interest rates cause inflation, so I think the numbers reflect how interest rates have chased inflation lower since the mid-eighties, in efforts to stoke investment and employment. The RBA and other central banks have gingerly ratcheted down rates, accompanied by inflationary doom-saying every step of the way.

To compensate for the long term upwards trend of CPI, I use its year-on-year change (i.e. inflation rate). When we treat interest rates the same way, i.e. using year-on-year change, we get:

Correlation (r): 0.22 - very weak positive, unexpected direction (OCR Change)

Still, less reflective of inflation responding to rates than of rate-setters responding (partially) to inflation.

I think we continue to associate inflation with interest rates because senior decision makers born in the 1940s - 1950s (baby boomers) came of age during two periods in the Anglosphere when inflation indeed ran strongly counter to rates. The first was the 1960s, when low rates and stimulatory government spending to rebuild after the Second World War and prepare for the Cold War was followed by ever-increasing inflation. The second being the late 1970s, when double-digit central bank interest rates in the U.S. appeared to bring inflation under control.

The floating of the Australian dollar in 1983 was followed by the crumbling of the exchange rate and a spike in inflation. The response was to hike interest rates to combat inflation and support the currency. Common wisdom is that it worked, with the price being an unavoidable recession.

A few historical instances have cemented interest rates as the cause of inflation, despite opposing evidence subsequently and internationally. This mindset will likely persist. Those who came of age in the 1990s and 2000s are not yet in positions of influence, nor are the recent cases of Japan (negative rates, low inflation) and Europe considered relevant by incumbents in power.

Some economists argue that increased government debt is not inflationary because contrary to popular belief, countries need not spend within their means like households.

A fair point. Inflation measures changes in household spending. And interest rates ripple through to household debt as well as affecting government borrowing.

So what does cheaper money do to households?

Bonus round: Inflation vs Household Debt 🏚

- Measures: CPI year-on-year % growth vs ...

- Household debt to GDP, October 2005 - January 2021, Quarterly

- Household debt to income, 1995-2019, Annual

- Expected relationship: positive

Self-styled conservatives fret that making borrowing cheaper will lead to more debt, which reckless households will use to drive up the price of everything.

They are partially correct.

1995 - 2019 Correlation (r): -0.03 - very weak, unexpected direction

2005

- 2021 Correlation (r): -0.63 - moderate, unexpected direction

Household debt has ballooned while inflation has stagnated.

Clearly fears that the public would leverage into jet skis en masse were unfounded.

Most household debt is housing debt. That is, mortgages and property loans.

Housing debt rocketed as house prices in Australia (and other developed countries) took off. With lower interest rates, buyers could afford bigger loans and sellers could ask for higher prices.

Houses, like shares, are considered assets, not consumer items. You don't pick up a house from the supermarket, and thus they are not included in the Consumer Price Index.

To include the cost of housing in consumption, statisticians impute rent. However, rents have not risen nearly as fast as house prices, and are only part of the decision to buy. House hunters consider lower rental yields in light of recent capital gains and for now still find the 'buy' argument compelling.

In short, inflation measures do not fully capture movements in house prices, to which the majority of household debt is applied.

Should the government have intervened? Perhaps they would have, had they not faced their own rising debt. Australian (and US - UK) public housing stock has declined since the 1980s, so government austerity could be seen as shifting some of the rising debt burden onto households, without which public debt would surely be much larger by now.

As well as house prices not registering as inflation, they could dampen it as Australian households spend more on their mortgage, and not so much on everything else. The RBA in 2019 found evidence of such debt overhang.

Estimates from our preferred specification suggest that a 10 per cent increase in debt reduces household expenditure by 0.3 per cent.

People applying cheaper credit to the roofs over their heads is hard to cast as irresponsible. Therefore, the hand-wringing about interest rate cuts likely masks another motive. Given that fiscal conservatives are by their nature likely to have larger cash piles, many are probably sore that they can no longer demand usurious risk-less interest on their bank deposits. Their thrift is being punished rather than rewarded, as interest that would otherwise effortlessly flow to them is stolen and converted into a discount to benefit those they consider less prudent (i.e. everyone else).

If that description sounds mean-spirited, well, what did you expect? We are talking about people on the miser spectrum, myself included, who might anyway take it as a compliment.

Inflation vs Currency 💱

- Measures: CPI year-on-year % growth vs Real Effective Exchange Rate (average) year-on-year % growth

- Period: 1985 to 2019, annual

- Expected relationship: negative (stronger dollar = less inflation)

What if we start looking outside Australia, to its freely floated, non-reserve currency?

The theory goes: less demand for the currency equals a weaker currency, imports get dearer, inflation ticks higher.

I've covered it already, but to save you a click:

Correlation (r): -0.24 - very weak

Inflation vs Trade ⚓

- Measures: CPI year-on-year % growth vs Balance of Trade

- Period: June 1985 to March 2021, quarterly

- Expected relationship: negative

Australian kids in the 1980s asked new migrant me, "Does your Dad drive a Ford or Holden?"

Both were locally made cars, with schoolyard debates as to which was superior centering on the availability of spare parts for the inevitable breakdowns.

It was either-or. No other choice.

Back in Singapore we drove the "Jap crap" Toyota, which half the kids in suburban Adelaide had not heard of and the other half didn't take seriously.

Their parents, they said, wouldn't trust a car they couldn't personally see roll off the line. (Perhaps taking the opportunity to point out assembly defects before delivery.) Australia exchanging produce for machinery, primarily to the UK and the US, was common knowledge, but trade was about to become more visible to ordinary Australian consumers.

From DFAT's "Fifty Years of Australia's Trade":

In the early 1980s, falling oil prices and contracting economic growth in the industrialised world, including Australia, slowed import growth until 1983-84 when economic reforms (including further reduction of import tariffs and quota protection) restored growth. Between 1983-84 and 1989-90 imports grew an average of 12.9 per cent per annum in value terms (7.5 per cent in volume terms).

With lower tariffs and Australia’s integration with the world economy, the share of Consumption goods has increased, now accounting for around 25 per cent of total imports. By sourcing Consumption goods from countries with cheaper manufacturing sectors, the price Australian’s pay for Consumption goods has decreased significantly.

Back to the cars. Imports of motor vehicles, parts & accessories went from $247m in 1963-64 to $17,834m for just passenger cars in 2013-2014. It wasn't just that you could get crappier cars for less money. The same amount of money would buy you a better car from Japan, and later Korea. And now you can't buy Holdens anymore.

The double hit of lower tariffs and price competition would surely dampen inflation, right?

Correlation (r): -0.12 - weak

Australians don't only consume imports. Cars, oil, and toys can come from overseas, but not homes, tuition, or surgeries. This limits how much imports affect inflation.

And while import flows weaken the dollar, inflating the cost of future imports, imports are only half of the picture.

Economic deregulation during the 1980s and 1990s opened Australia’s economy to the world and combined with new investment and global demand, contributed to strong export growth that continued over the next two decades. Growth through the period averaged 9.8 per cent per annum in value terms and volume growth recovered to 7.1 per cent per annum.

Australia's balance of trade is tilted towards exports, strengthening the dollar.

When you consider the interplay of imports, exports, and currency (treated separately) the muted effect is no surprise.

Inflation vs Industrial Action ⚒

- Measures: CPI year-on-year % growth vs Number of Industrial Disputes

- Period: June 1985 to March 2021, quarterly

- Expected relationship: positive

The ability to strike or conduct industrial action is central to worker bargaining power, particularly when negotiating wage rises to keep up with price rises, (hopefully without triggering wage-price spirals).

I use the number of industrial disputes in a given period as a proxy for the power of labour.

Striking wasn't always legal. It wasn't illegal either.

Until recently in Australia, trade unions could be sued for damages arising from a strike. This threat was clearly not discouraging and they liberally rolled the lawsuit dice.

Industrial action was used for activism as well as improving working conditions.

In 1976 the Waterside Workers Federation stopped the shipment of goods to apartheid South Africa.

The Builders Labourers Federation's (BLF) 'Green Bans' impeded the destruction of environmentally and culturally significant sites in Melbourne and Sydney.

If you can't strike for anything, you may as well strike for everything.

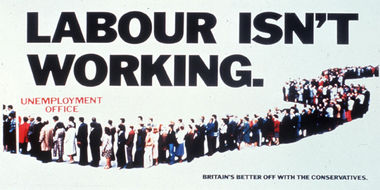

Strikes were big across the Anglosphere too.

Coal miners brought down a Tory government, and sympathetic strikes left the empire's capital choking with rubbish. The 1970s also saw strikes in almost every employment category in the U.S., from auto-workers to postal workers.

Public sentiment turned - or was turned - against striking unionists. Corruption tarnished the BLF's image as conscientious political actors, allowing for their portrayal as self-serving and obstructionist. In the UK, the disruption resulting from industrial action was leveraged to win Margaret Thatcher power. Ronald Reagan stared down and fired the striking air traffic controllers who threatened to ground the nation.

In 1993, the Keating government allowed 'protected actions' in Australia. Unions fell in line as newly-legitimate industrial action was now less risky. The catch? Stiff penalties for unprotected actions. So no more striking for causes outside your immediate workplace, no matter how worthwhile they were.

Subsequent governments, particularly the Howard government, tightened protected actions and industrial relations laws in general.

Correlation (r): 0.77 - strong positive

Now would be a good time to remember that correlation is not causation. The causative direction could run the other way; slowing inflation may have obviated the need to strike. The relationship may in fact be due to a third factor, or coincidental.

Change in the number of industrial actions year-to-year has almost no correlation (r = 0.05) with year-on-year inflation, casting doubt as to whether a link exists.

One more reason to be sceptical is the weak relationship (r = -0.24) between trade union membership levels and inflation. (Australia, 1992-2013, annual).

Disclaimer out of the way, industrial action conceivably causes inflation through two mechanisms: increasing labour costs which get passed on through higher prices, as well as constricting the supply of goods and services.

Labour strength coincides with inflation not when it is merely wielded, but when it is exercised.

Comments

Post a Comment